Translated and edited by Philip Pullman

Published by Penguin

|

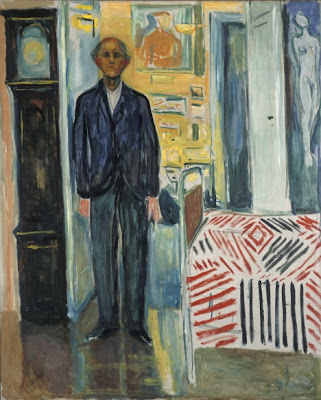

| Watts' nineteenth century image of Little Red Riding Hood. From here. Charles Dickens apparently claimed she was his first love... |

A selection of the best of the disturbing tales recounted to the Grimms, elegantly transated and with an insightful commentary.

Although they are usually called ‘fairy tales’ in English, I

prefer the original Grimm title, translated here as ‘folk and house tales’,

though I believe the term has a broader meaning of ‘community tales’. And this

is how I read them – not primarily as stories aimed for an audience of children.

These short stories are unsophisticated, and even the best

are very slight works of art. Many have the kernel of greater artworks within

them (most famously Snow White and Cinderella, but even better Hansel and Gretel), or they have tapped into such a universal nightmare that, like the

tales of Poe, they can be retold in powerful variants (Little Red Riding Hood).

But the greatest interest for me in these tales is that they

surely reflect certain attitudes in communities centuries ago, with which we now

find difficulty empathising. Hierarchies appear divinely ordained, with kings

only rarely questioned. These are stories with what could be described as an authoritarian setting, though the anarchic elements could equally be seen as subverting this setting, albeit weakly.

And the family unit is as often a source of abuse as comfort, with parents all the way up the social ladder acting appallingly to their children.

And the family unit is as often a source of abuse as comfort, with parents all the way up the social ladder acting appallingly to their children.

For these reasons, and others, the Grimm brothers and their

successors linked these tales to a medieval, proto-nationalistic mindset. As

the nationalism concerned was German, we now find the Grimms’ ideas as

difficult as the assumptions lurking in the tales themselves.

This may explain why Philip Pullman doesn’t address these

aspects in his otherwise informative introduction to this selection of 50 of

the tales. Perhaps he also wants to avoid a sociological reading of the tales, as

this can seem to compete with the basic joy of the storytelling. Nonetheless,

in describing some of the aspects of the stories, such as their lack of

psychological depth, I felt some of the uncanniest aspects are precisely those

that might seem sociological.

Put a different way, some of the strongest, strangest

experiences when reading these tales are not covered by Pullman in his

introduction. This is a serious omission – I think the reception of these tales, and how they continue to influence our view of the medieval, despite being transcribed in the nineteenth century, are intrinsic to their literary value.

Otherwise, the book is wonderful. Pullman succeeds in

translations that are ‘clear as water’ and happily adapts the stories whenever

he feels he can do a better job… so this edition is not suitable for pedants.

The comments at the end of each story are worth the price of

the book in themselves, as we get the editor’s views on why and how the story

works, what weaknesses it might contain, and so on. And it struck me that

everyone would benefit from these notes, pedants or not.