Tate Modern, 28 June - 14 October 2012

|

| Edvard Munch: Self-portrait. The night wanderer. 1923-4. Munch museet. |

A major Tate Modern exhibition serves to reveal its subject

as a latecomer rather than an innovator, despite its claims.

Sometimes curators claim too much for their subject, and

here is a case study. Whatever might be said of Munch, I saw nothing in this

exhibition to suggest he was a precursor of modernism, or modern in any other

significant respect, aside from the fact he died in 1944.

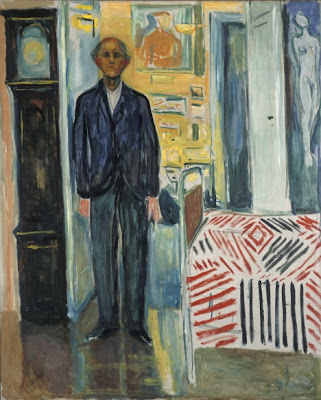

The curators claim

his aged self-portraits are unflinching depictions of his fragility, yet

whether he had just experienced a life threatening illness, or was so old that

death must have seemed imminent, Munch consistently portrayed himself as a

hero, intense, stoic, resolute.

|

Edvard Munch: Self-Portrait: Between the Clock and the Bed 1940–3

Munch Museet

|

On the evidence of this exhibition, which

collects photographs, woodcuts, prints, drawings, paintings, sculptures, even

amateur films, the artist’s self image was the same throughout his life, at all

ages.

Given the failure of these curators to make him modern, I

feel confident in asserting that Munch was a late Romantic, in fact a Decadent,

his whole life, regardless of the changes that surrounded him.

Almost

everything about his art confirms that he was born too late, with the partial

exception of his chosen media, though it is clear his reputation will continue

to rest on his paintings rather than his photography and films.

Some of the rooms are impressive despite contradicting the

curatorial plan. A room of some of his more well-known paintings in early and

later incarnations is interesting. Munch compulsively repainted his earlier

ideas, though I think the general rule is: earlier is better.

Perhaps as time

passed and he became more detached from his preferred period, which is clearly

the late Romantic twilight of vampires, screams, nights and forests, the harder

it became to recapture his original inspiration.

Well then, a belated figure. How does he stand, considering

his concerns in themselves, so far as we can assess this? Pride, obsession,

angst: these are his High Romantic themes, and as we might expect from a

decadent version of romanticism, his art induces unease, claustrophobia,

spleen, even nausea.

Colours clash; faces (or masks of such) are prominent;

viewpoints are vertiginously dramatic. The exhibition is useful in showing he had more ways of achieving these effects than I thought. Not everything is wibbly-wobbly.

Having a characteristic approach is a strong selling point

for an artist, and Munch had that. But if we compare him with his older

contemporary, Ibsen, for whose dramas he sometimes produced scenery, we

discover his limitations. Munch’s best paintings reflect our doubts, our fears.

Ibsen takes this basic material and uses it to investigate how we might

overcome these anxieties, whether successfully or not.

No comments:

Post a Comment